Analytic capacity

In complex analysis, the analytic capacity of a compact subset K of the complex plane is a number that denotes "how big" a bounded analytic function from  can become. Roughly speaking,

can become. Roughly speaking,  measures the size of the unit ball of the space of bounded analytic functions outside K.

measures the size of the unit ball of the space of bounded analytic functions outside K.

It was first introduced by Ahlfors in the 1940s while studying the removability of singularities of bounded analytic functions.

Contents |

Definition

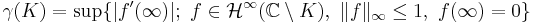

Let  be compact. Then its analytic capacity is defined to be

be compact. Then its analytic capacity is defined to be

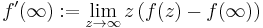

Here,  denotes the set of bounded analytic functions

denotes the set of bounded analytic functions  , whenever U is an open subset of the complex plane. Further,

, whenever U is an open subset of the complex plane. Further,

(note that usually  )

)

Ahlfors function

For each compact  , there exists a unique extremal function, i.e.

, there exists a unique extremal function, i.e.  such that

such that  ,

,  and

and  . This function is called the Ahlfors function of K. Its existence can be proved by using a normal family argument involving Montel's theorem.

. This function is called the Ahlfors function of K. Its existence can be proved by using a normal family argument involving Montel's theorem.

Analytic capacity in terms of Hausdorff dimension

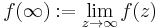

Let  denote Hausdorff dimension and

denote Hausdorff dimension and  denote 1-dimensional Hausdorff measure. Then

denote 1-dimensional Hausdorff measure. Then  implies

implies  while

while  guarantees

guarantees  . However, the case when

. However, the case when  and

and ![H^1(K)\in(0,\infty]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2d03d94a6585bcf59e31b82d02b8c59c.png) is more difficult.

is more difficult.

Positive length but zero analytic capacity

Given the partial correspondence between the 1-dimensional Hausdorff measure of a compact subset of  and its analytic capacity, it might be conjectured that

and its analytic capacity, it might be conjectured that  . However, this conjecture is false. A counterexample was first given by A. G. Vitushkin, and a much simpler one by J. Garnett in his 1970 paper. This latter example is the linear four corners Cantor set, constructed as follows:

. However, this conjecture is false. A counterexample was first given by A. G. Vitushkin, and a much simpler one by J. Garnett in his 1970 paper. This latter example is the linear four corners Cantor set, constructed as follows:

Let ![K_0:= [0,1]\times[0,1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/da042de16a6faddce0996834b695ad55.png) be the unit square. Then,

be the unit square. Then,  is the union of 4 squares of side length

is the union of 4 squares of side length  and these squares are located in the corners of

and these squares are located in the corners of  . In general,

. In general,  is the union of

is the union of  squares (denoted by

squares (denoted by  ) of side length

) of side length  , each

, each  being in the corner of some

being in the corner of some  . Put

. Put

Then  but

but

Vitushkin's Conjecture

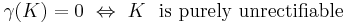

Suppose  and

and  . Vitushkin's conjecture states that

. Vitushkin's conjecture states that

In this setting, K is (purely) unrectifiable if and only if  for all rectifiable curves (or equivalently,

for all rectifiable curves (or equivalently,  -curves or (rotated) Lipschitz graphs)

-curves or (rotated) Lipschitz graphs)  .

.

Guy David published a proof in 1998 for the case when, in addition to the hypothesis above,  . Until now, very little is known about the case when

. Until now, very little is known about the case when  is infinite (even sigma-finite).

is infinite (even sigma-finite).

Removable sets and Painlevé's problem

The compact set K is called removable if, whenever Ω is an open set containing K, every function which is bounded and holomorphic on the set Ω\K has an analytic extension to all of Ω. By Riemann's theorem for removable singularities, every singleton is removable. This motivated Painlevé to pose a more general question in 1880: "Which subsets of  are removable?"

are removable?"

It is easy to see that K is removable if and only if  . However, analytic capacity is a purely complex-analytic concept, and much more work needs to be done in order to obtain a more geometric characterization.

. However, analytic capacity is a purely complex-analytic concept, and much more work needs to be done in order to obtain a more geometric characterization.

References

- Mattila, Pertti (1995). Geometry of sets and measures in Euclidean spaces. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65595-1.

- Pajot, Hervé (2002). Analytic Capacity, Rectifiability, Menger Curvature and the Cauchy Integral. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. Springer-Verlag.

- J. Garnett, Positive length but zero analytic capacity, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 21 (1970), 696-699

- G. David, Unrectifiable 1-sets have vanishing analytic capacity, Rev. Math. Iberoam. 14 (1998) 269-479